![\resizebox*{1.0\columnwidth}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{fig/PacketSwitchFunctionality}}](pmf_thesis_img1.png)

|

In order to understand the technology trends to compare them to those of traffic, one has to know the functions that packet and circuit switches do, and the technology used to perform them. In the following, I will focus on the switching function (i.e., the forwarding of information) in a network node. Figure 1.1 shows the functional blocks of a packet switch, also called a router. When information arrives at the ingress linecard, the framing module extracts the incoming packet from the link-level frame. The packet then has to go through a route lookup to determine its next hop, and the egress port [82]. Right after the lookup, any required operations on the packet fields are performed, such as decrementing the Time-To-Live (TTL) field, updating the packet checksum, and processing any IP options. After these operations, the packet is sent to the egress port using the router's interconnect, which is rescheduled every packet time. Several packets destined to the same egress port could arrive at the same time. Thus, any conflicting packets have to be queued in the ingress port, the output port, or both. The router is called an input-queued switch, an output-queued switch, or a combined input/output-queued switch depending on where buffering takes place [123].

In the output linecard, some routers perform additional scheduling that is used to police or shape traffic, so that quality of service (QoS) guarantees are not violated. Finally, the packet is placed in a link frame and sent to the next hop.

In addition to the data path, routers have a control path that is used to populate the routing table, to set up the parameters in the QoS scheduler, and to manage the router in general. The signaling of the control channel is in-band, using packets just as in the data channel. The control plane might obtain the signaling information through a special port attached to the interconnect.

The main distinction between a router and a circuit switch is when information may arrive to the switch. In packet switching, packets may come at any time, and so routers resolve any conflicts among the packets by buffering them. In contrast, in circuit switching information belonging to a flow can only arrive in a pre-determined channel, which is reserved exclusively for that particular flow. No conflicts or unscheduled arrivals occur, which allows circuit switches to do away with buffering, the on-line scheduling of the interconnect, and most of the data-path processing. Figure 1.2 shows the equivalent functions in a circuit switch. As one can see, the data path is much simpler.

In contrast, the control plane becomes more complex: it requires new signaling for the management of circuits, state associated with the circuits, and the off-line scheduling of the arrivals based on the free slots in the interconnect. Usually there is a tradeoff between the signaling/state overhead and the control that we desire over traffic; the tighter the control, the more signaling and state that will be needed. However, in circuit switching, as in packet switching, a slowdown in the control plane does not directly affect the data plane, as all on-going information transmissions can continue at full speed. In general, its data path determines the capacity of the switch.

Another important difference between a router and a circuit switch is the time scale in which similar functions need to be performed. For example, in both types of switches the interconnect needs to be scheduled. A packet switch needs to do it for every packet slot, while a circuit switch only does it when new flows arrive. In general, a flow carries the same amount of information as several packets, and thus packet scheduling needs to be faster than circuit scheduling.

In order to study how the capacity of links and switches will scale in the future, one needs to understand the evolution trends of the underlying technologies used in routers and circuit switches. This enables one to foresee where bottlenecks might occur.

Below, I will focus on the data path of a router, since the data path of a circuit switch is just a subset of it. In general, a router has to:

To study the performance trends, I will focus on the core of the network, where traffic aggregation stresses network performance the most. The core also uses the state of the art in technology because costs are spread among more users. The backbone of the Internet is built around three basic technologies: silicon CMOS logic, DRAM memory, and fiber optics.

As was mentioned before, Internet traffic has been doubling every year since 1997.1.2 In contrast, according to Moore's law, the number of functions per chip and the number of instructions per second of microprocessors have historically doubled every 1.5 to 2 years1.3 [3,144]. Historically, router capacity has increased slightly faster than Moore's law, multiplying by 2.2 every 1.5 to 2 years. This has been due to advances in router architecture [123] and packet processing [82].

DRAM capacity has quadrupled on average every three years, but its frequency for consecutive accesses has been increasing less than 10% a year [144,143], equivalent to doubling every 7 to 10 years. Modern advanced DRAM techniques, such as Synchronous Dynamic RAM (SDRAM) and Rambus Dynamic RAM (RDRAM), are attacking the problem with I/O bandwidth across pins of the chip, but not the latency problem [58]. These techniques increase the bandwidth by writing and reading bigger blocks of data at a time, but they cannot speed up the time it takes to reference a new memory location.

Finally, the capacity of fiber optics has been doubling every 7 to 8 months since the advent of DWDM in 1996. However, the growth rate is expected to decrease to doubling every year as we start approaching the maximum capacity per fiber of 100 Tbit/s [124]. Despite this future growth slowdown of DWDM, the long-term growth rate of link capacity will still be above that of Internet traffic at least past the year 2007 [116].

Figure 1.3 shows the mismatch in the evolution rates of optical forwarding, traffic demand, electronic processing, and electronic DRAM memories. We can see how link capacity will outpace demand, but how electronic processing and buffering clearly drag behind demand. Link bandwidth will not be a scarce resource, but the information processing and buffering will be. Instead of optimizing the bandwidth utilization, we should be streamlining the data path.

![\resizebox*{0.8\columnwidth}{!}{\includegraphics[clip]{fig/MooresLaws}}](pmf_thesis_img3.png)

|

Figure 1.3 shows how there is an increasing performance gap that could cause bottlenecks in the future. The first potential bottleneck is the memory system. Routers may be able to avoid it by using techniques that hide the increasingly high access times of DRAMs [91], similarly to what modern computers do. With these techniques access times come close to those of SRAM, which follows Moore's law. However, they make buffering more complex, with deeper pipelining, longer design cycles and higher power consumption.

The second potential bottleneck is information processing. The trend would argue for the simplification of the data path. However, there is a lot of pressure from carriers to add more features in the routers, such as intelligent buffering, quality-of-service scheduling, and traffic accounting.

If we keep the number of operations per packet constant, in ten years time, the same number of routers that we currently have will be able to process 200 times as much traffic as today. In contrast, traffic will have grown 1000 times by then. This means that we will have a five-fold performance gap. In ten years time we will need five times more routers as today. These routers will consume five times more power, and will occupy five times more space.1.4 This means building over five times as many central offices and points of presence to house them, which is a very heavy financial burden for the already deeply indebted network carriers. To make matters worse, a network with more than five times as many routers will be more complex and more difficult to manage and evolve. The economical and logistical cost of simply adding more nodes is prohibitive, so we need to be creative, and think out of the box, trying to find a more effective solution that solves the mismatch between traffic demand and router capacity, even if it represents a paradigm shift.

One possible solution is to use optical switching elements. Optics is already a very appealing technology for the core because of their long reach and high capacity transmission. Additionally, recent advances in MEMS [15,83], integrated waveguides [85], optical gratings [101,27], tunable lasers [187], and holography [149] have made possible very high capacity switch fabrics. For example, optical switches based on MEMS mirrors have shown to be almost line-rate independent, as opposed to CMOS transistors, which saturate before reaching 100 GHz [3,130]. Ideally, we would like to build an all-optical packet switch that rides on the technology curve of optics. However, building such a switch is not feasible today because packet switching requires buffers in order to resolve packet contention, and we still do not know how to buffer photons while providing random access. Current efforts in high-speed optical storage [178,109,151] are still too crude and complex. In current approaches, information degrades fairly rapidly (the longest holding times are around 1 ms), and they can only be tuned for specific wavelengths. It is hard to see how they could achieve, in an economical manner, the high integration and speed that provides 1.2 Gbytes of buffers to a 40 Gbit/s linecard.1.5

Another problem with all-optical routers is that processing of information in optics is also difficult and costly, so most of the time information is processed electronically, and only the transmission, and, potentially, the switching is done in optics. Current optical gates are all electrically controlled, and they are either mechanical (slow and wear rather quickly), liquid crystals (inherently slow), or poled LiNbO3 structures (potentially fast, but requiring tens of kV per mm, making them slow to charge/discharge). Switching in optics at packet times, which can be as small as 8 ns for a 40 Gbit/s link, is very challenging, and, thus, there have been proposals to switch higher data units [188], called optical bursts. Rather than requiring end hosts to send data in larger packets, these approaches have gateways at the ingress of the optical core that aggregate regular IP packets into mega-packets. These gateways perform all the buffering that otherwise would be performed in the optical core, so the buffering problem is not eliminated, but rather pushed towards the edges.

In summary, all-optical routers are still far from being feasible. On the contrary, all-optical circuit switches are already a reality [15,111,112,174,54,32]. This should not be a surprise, since circuit switching presents a data path that requires no buffering and little processing. For example, Lucent has demonstrated an all-optical circuit switch, using MEMS mirrors, with switching capacities of up to 2 Pbit/s [15]; this is 6000 times faster than the fastest electronic router [94].

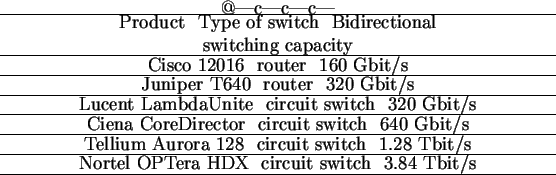

Even when we consider electronic circuit switches and routers, the data path of circuit switches is much simpler than that of electronic routers, as shown in Figure 1.1 and Figure 1.2. This simple data path of circuit switches allows them to scale to higher capacity than equivalent electronic routers. This is confirmed by looking at the fastest switches and routers that are commercially available in the market at the time of writing; one can see that circuit switches have a capacity that is 2 to 12 times bigger than that of the fastest routers, as shown in Table 1.1. The simple data path of circuit switches comes at the cost of having a more complex control path. However, it is the data path that determines the switching capacity, not the control path; every packet traverses the data path, whereas the control path is taken less often, only when a circuit needs to be created or destroyed.

|

In this Thesis, I argue that we could close the evolution gap between Internet traffic and switching capacity by using more circuit switching in the core, both in optical and electronic forms. I also explore different ways of how one could integrate these two techniques.